Ensuring the Resilience of Seagrass Meadows

Learning to manage the habitats and biodiversity within our oceans and coasts is one of the greatest challenges of this century.

Image: By Claire Fackler, CINMS, NOAA. (NOAA Photo Library: sanc0067) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Image: By Claire Fackler, CINMS, NOAA. (NOAA Photo Library: sanc0067) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons By Dr Richard Unsworth, Swansea University.

Our oceans and coasts are changing rapidly due to human impacts with habitats and animal populations in sharp decline. One such habitat is that provided by seagrass which we know to be in rapid decline worldwide. The major problem with this loss is that our very existence depends on the resources and functions that biodiversity and productive habitats provide. Learning to manage the habitats and biodiversity within our oceans and coasts is one of the greatest challenges of this century.

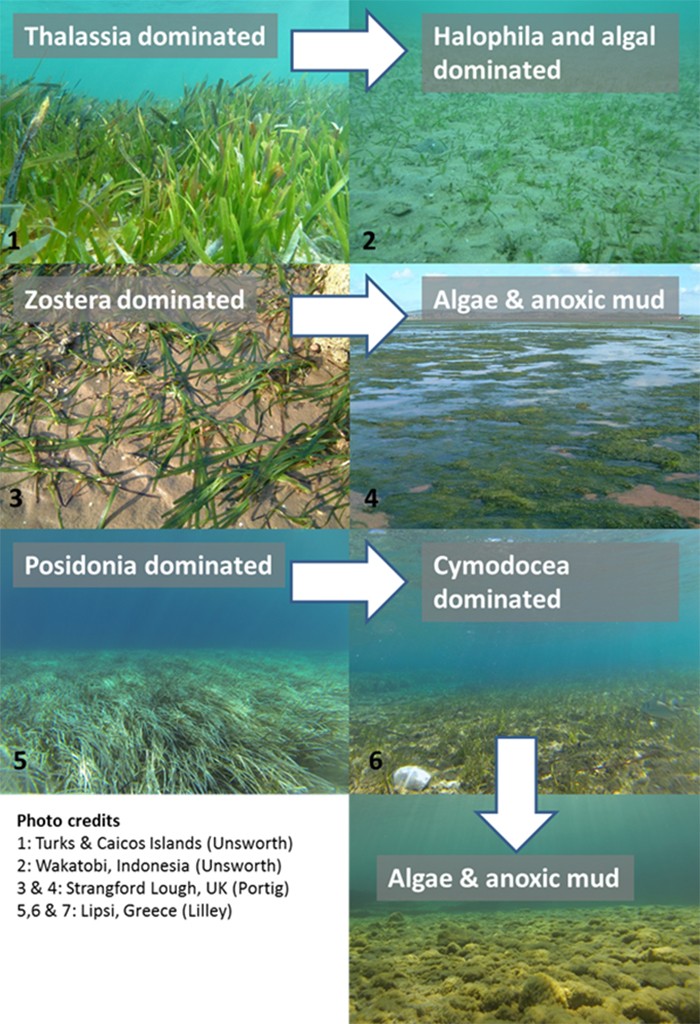

Seagrass meadows are the ‘Prairies of the Sea’. They are highly productive shallow water marine and coastal habitats comprised of marine plants. These threatened habitats provide important food and shelter for animals in the sea. Seagrass meadows provide a range of ecosystem services to the human planet such as nursery areas for juvenile fish, production of oxygen, coastal defence, and storage of carbon dioxide. For example, seagrass meadows in the North Atlantic are a key nursery ground for Atlantic Cod as they provide great habitat for them to be safe from predation and to have an easily accessible source of abundant invertebrate food. When seagrass is damaged it often goes from being a productive habitat full of animal life to one that is lifeless and smothered by thick algae (see fig 1).

figure 1

Management of our coasts typically takes the approach of establishing Marine Protected Areas, controlling fishing, or regulating industrial activity. But in the face of the increasing threat of climate change to habitats such as seagrass we need to take measures that increase the resilience of our important habitats to ensure they survive into the future (Ecological resilience is “the capacity of an ecosystem to absorb repeated disturbances or shocks and adapt to change without fundamentally switching to an alternative stable state”).

This week (together with scientists at Cardiff University, James Cook University and University of Adelaide) we’ve published new research in the journal Marine Pollution Bulletin that examines the ecosystem resilience of seagrass meadows globally. The work shows how the resilience of these productive ecosystems is becoming compromised by a range of local to global disturbances and stressors, resulting in ecological regime shifts that undermine their long-term viability.

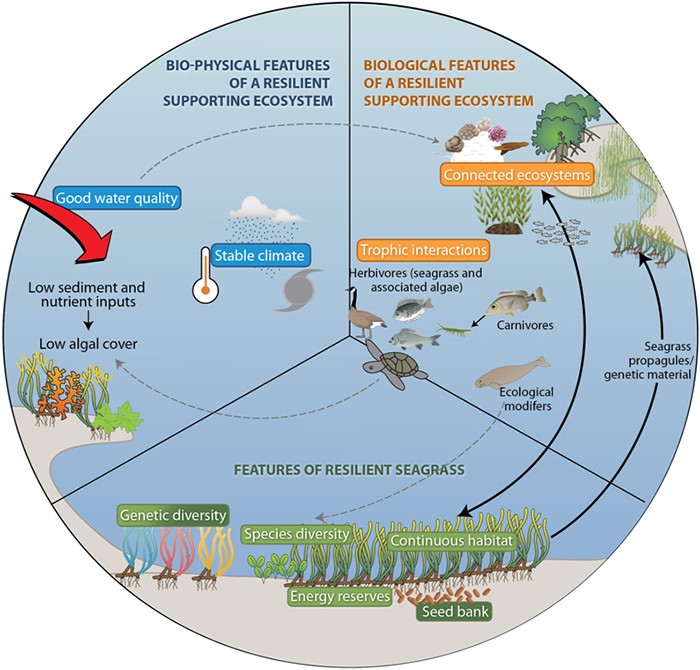

The research examined over 150 sources in the academic literature and illustrates how the management of seagrass meadows needs to consider a series of features and modifiers that act as interacting influences on the resilience of the ecosystem (see fig 2). The resilience of seagrass meadows is influenced by many factors, such as the health and proximity of adjacent habitats; the water quality; the supply of pollen and larvae, and the presence of human disturbance. Management of biodiverse and important marine ecosystems like seagrass needs to consider more than just simple location specific protection, but instead consider the biological and environmental influences beyond the extent of its distribution.

figure 2

It is a lot easier to protect what we have than to try and restore these systems at great cost in the future. A series of simple actions by marine conservation managers can help to improve ecosystem resilience, such actions include reducing local disturbance to the seagrass (e.g. destructive fishing, use of anchors), conducting specific fisheries management actions to ensure a balanced food web, considering planned restoration in locations of seagrass loss, or improving local people’s knowledge of the value, sensitivity and locality of their meadows. We believe that seagrass meadows can survive into the future but action has to be taken to make the necessary changes to ensure these wonderful habitats remain part of our coastline. It is for these reasons that a group of scientists at Swansea University and Cardiff University have launched a charity called Project Seagrass that aims to push forward seagrass conservation.

2 Comments

I found this article extremely interesting as I have

Researched and executed a similar project myself focusing on estuaries. If you would like any help please feel free to contact me.

Kind regards

Sarah-Jayne

Being a M.S.degree holder in ecology, with my dissertation on the sea grass Halophila ovalis, I wish to state that seagrass restoration is the need of the other and would like to work with payment in any of your projects in the future.