G is for Glow worm

The gentle green glow which gives this special insect its name emanates from the lower abdomen of females on summer evenings, peaking in June and July.

Image: Chris Foster

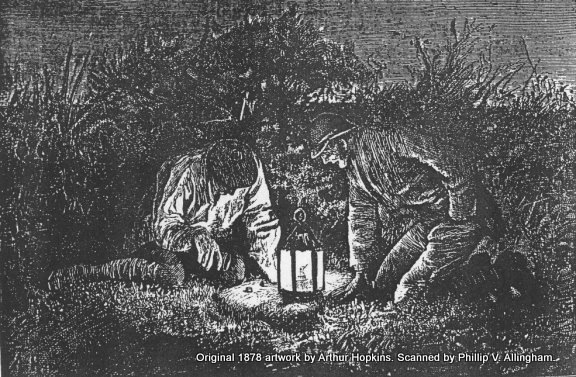

Image: Chris Foster Glow worms are not actually worms at all, but beetles. The gentle green glow which gives this special insect its name emanates from the lower abdomen of females on summer evenings, peaking in June and July. Completely flightless, the larvae-like females spend most of their adult lives in one small area and display in the same location each night, waiting for a passing male – winged and more stereotypically like a beetle– with which to mate. Once mating has occurred, the female turns off her light for the last time, lays eggs and dies. A few weeks later the larvae hatch: voracious consumers of snails, they can grow as large as adults, and will live for one to three years. Larvae are perhaps easiest to see when they’re crossing open muddy or rocky ground between patches of vegetation, such as a path (pictured). They can glow in the same way that females do, but do so feebly and intermittently, perhaps as a defence against predators.

The above image is courtesy of The Victorian Web: http://www.victorianweb.org/art/illustration/hopkins/7.html

The general sense is that there aren’t nearly as many glow worms as there used to be, a feeling cultivated by half-remembered folk tales about being able to read a book in country lanes by glow worm light alone, or by the famous scene in Thomas Hardy’s 1878 novel The Return Of The Native, in which glow worms are used to illuminate a game of dice. But considering the rather fragile light emitted by a single glowing female, it would have taken a lot even to match the brightness of a single candle flame. It seems unlikely that enough ever lit up the British countryside simultaneously that they served as a usable light source. And it has been pointed out that since it took Hardy’s gamblers a few minutes to collect as many as a dozen they can’t have been entirely ubiquitous even in rural ‘Wessex’.

By Timo Newton-Syms from Chalfont St Giles, Bucks, UK (Glow worm) [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

What seems more likely is that glow worms have never been all that abundant, but that habitat destruction and interference from artificial lighting has also resulted in a general decline in recent decades, destroying some colonies and depleting others. That said, long running site surveys show a large natural variation in numbers from year to year, and when colonies do vanish the reason why is not consistent. And the UK Glow Worm Survey has found that they remain more widespread than was perhaps thought, still viewable in hundreds of locations across the country.

So it could be that the story of the glow worm’s apparent decline is not necessarily just about numbers, but reflects our diminishing experience of nature. The sorts of places the human inhabitants of Britain spend time outdoors at night – mostly over-lit, over-mown, tidy suburban gardens – do not make for good glow worm habitat. Maybe we have lost touch with our illuminating little friends and dismissed them as creatures of the romantic past, not relevant to the present. Or in our busy modern lives, we may simply be forgetting to go look for them at all. It would be a shame if that were true.

Follow UK glow worms on twitter! @ukglowworms.

The name glow worm has been given to other bioluminescent insects around the world, including a remarkable group of fungus gnats (one species in North America and some in Australasia) whose predatory larvae glow blue as a means of luring prey. More familiar to American readers will be fireflies, a glow worm relative often seen lighting up in flight over lawns on summer evenings. All of these insects use similar chemical processes to produce light, but apparently evolved the ability quite independently of each other.

No comments yet.