How will Climate Change Affect the North Atlantic Current?

Core samples have shown us that the last ice age caused the North Atlantic Drift to slow down, but it is thought that its path changed between then and now. However, the study of past climate shows that the Gulf Stream has stopped completely several times in the past, causing rapid climate change.

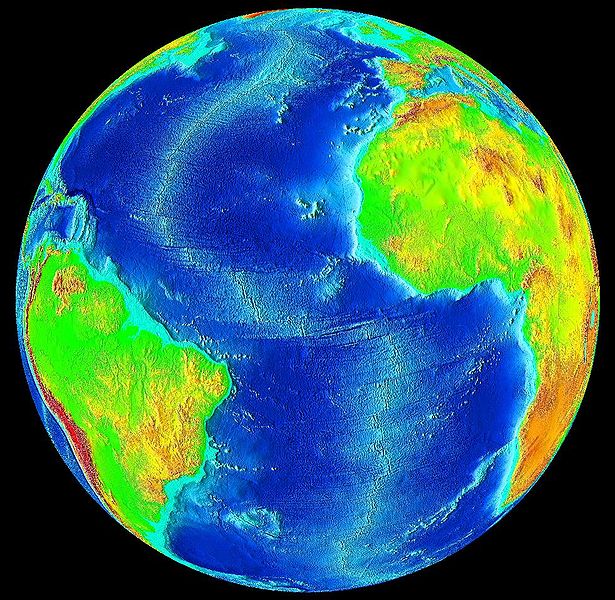

Image: This image is in the public domain because it is a screenshot from NASA’s globe software World Wind using a public domain layer, such as Blue Marble, MODIS, Landsat, SRTM, USGS or GLOBE.

Image: This image is in the public domain because it is a screenshot from NASA’s globe software World Wind using a public domain layer, such as Blue Marble, MODIS, Landsat, SRTM, USGS or GLOBE. The North Atlantic Current (otherwise known as North Atlantic Drift and North Atlantic Sea Movement) is a major warm ocean current that is part of the Gulf. West of Europe it splits into two major branches. One branch goes to the south-east, and becomes the Canary Current, passing north-west Africa and turning south-west. The other major branch of the North Atlantic Current continues north and follows the coast of north western Europe. The whole of the North Atlantic Current contributes greatly to the warming of the climate and has a huge influence on British weather. Other branches coming off the current include the Irminger Current and the Norwegian Current.

A climatology lecturer of mine once told me that the cold water coming off the melting icecaps may shut down or slowdown the thermohaline circulation of the North Atlantic current. This could trigger localised cooling in the North Atlantic, particularly affecting countries such as Ireland, Britain and the Nordic countries that are warmed by the North Atlantic drift. The chances of this occurring are unclear; there is some scientific evidence for the stability of the Gulf Stream but also a weakening of the North Atlantic drift. However there is also evidence of warming in northern Europe and nearby oceans, rather than the reverse (which would be expected if this theory is correct). Once this was pointed out to him, he stated that the cold water may cause the current to ‘switch off’ rather than cool down slowly. Core samples have shown us that the last ice age caused the North Atlantic Drift to slow down, but it is thought that its path changed between then and now. However, the study of past climate shows that the Gulf Stream has stopped completely several times in the past, causing rapid climate change.

What would this mean for Britain and Ireland?

First of all, if the climate causes the North Atlantic Drift to slow down then the British and Irish winters would be up to 5°C colder. Studies have shown that even though the rest of the planet was warming up, the North Atlantic region remained in that cold period for up to 1300 years. This cooling happened around 8000 years ago and the cooling lasted about a hundred years. It is thought to be likely that this could happen again. Even a short period of cooling in the North Atlantic could have a dramatic effect on the wildlife, and the human populations, living there.

2 Comments

what are the chances given the rapidly melting ice sheets? Are we talking decades or milenia

riky ol boy it would have to be around 450 years