International Plans To Reduce Global Fisheries Crime

Whilst jail sentences and fines do already exist to discourage illegal activity, it is hoped this working group will help better enforce law at an international level.

Image: Luc Viatour / www.Lucnix.be [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC-BY-SA-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Image: Luc Viatour / www.Lucnix.be [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC-BY-SA-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons The fact we are over exploiting the world’s fish stocks has increasingly been in the news. For example, in the UK Hugh’s Fish Fight highlighted just how outdated the European Common Fisheries Policy is in regards to discards. With stocks dwindling we cannot just let fish be thrown away which are over the quota granted. In fact the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) has estimated that 70% of fish stocks are being fully or over exploited.

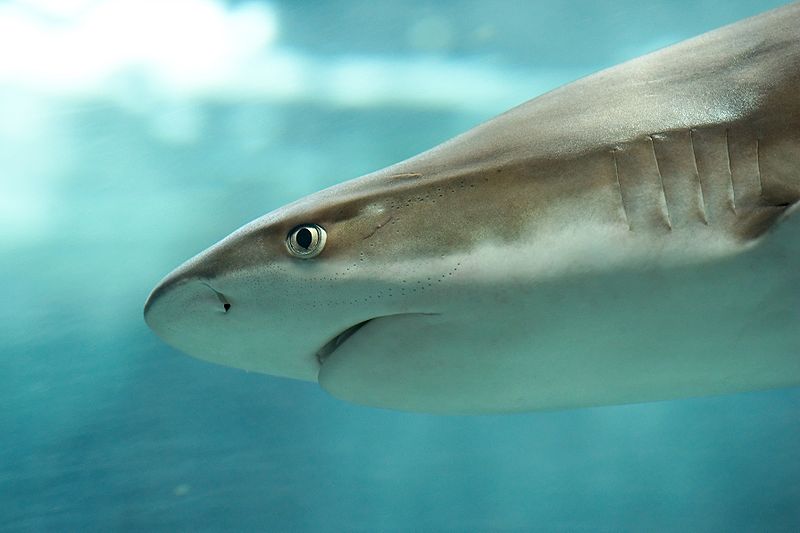

The demand for shark fin soup has led to shark populations falling dramatically around the world, with only a few countries banning the practice. Where it is banned, it can be hard to enforce, or there may be loopholes in the legislation. In countries where many live below the poverty line, such as Mozambique, shark finning is often seen as a vital source of income. Fins from just one shark can fetch $120 according to Shark Angels.

However, it isn’t just locals who fish illegally in order to survive. Global fisheries crime is a big industry, with the impact of illegal fishing on fish stocks estimated to be between $10 and $23.5 billion annually. But, what is actually being done on a global scale to tackle fisheries crime? A new paper in Conservation Biology highlights exactly this. ‘Catching Up on Fisheries Crime’ by Henrik Osterblom looks at how global fisheries crime is carried out and how it is being tackled at an international level.

Osterblom notes that fisheries crime, mainly in the form of illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing has led to unsustainable harvests. Quotas are being met by fishermen acting within the law, but IUU fishing is then taking further from fish stocks. One particular challenge is that fisheries crime is often linked to transnational organised crime. Some boats illegally fishing are being tipped off when marine reserve patrol boats are in the area. In other circumstances paperwork is forged, claiming fish were caught in areas where fishing is permitted. In many less economically developed countries authorities can simply be paid off with bribes.

With fish being shipped all over the world once caught, the paper emphasises that a global approach is important. However, so that regional issues which lead to fisheries crime can be tackled there is a need for regional fisheries management organisations. These can help monitor fish stocks, protect marine conservation zones and also address poverty.

The setup of the International Monitoring, Control and Surveillance (IMCS) network in 2001 was aimed to improve networking between countries. Unfortunately the IMCS network has only started working well since 2012 when it was formally recognised by the Committee on Fisheries, a subsidiary of the FAO. Nevertheless three Global Fisheries Enforcement Training Workshops setup by the IMCS network have provided vital opportunities to find out about the latest methods and technologies to address fisheries crime.

In the EU the European IUU regulation in 2010 was the first major step towards tackling the problem posed by IUU in European waters. This regulation requires lists of IUU vessels and substantial penalties for those caught carrying out IUU fishing.

On a global level INTERPOL, the world’s largest police organisation, established a Fisheries Crime Working Group (FWCG) in 2012. Whilst jail sentences and fines do already exist to discourage illegal activity, it is hoped this working group will help better enforce law at an international level.

Despite initial teething problems with international legislation, it does look like global fisheries crime could soon be in decline. Collaboration is needed, but it can only work where organisations are working to achieve shared goals. In this respect, the IMCS network provides the knowledge to tackle crime, and the FCWG prosecutes anyone found guilty of fisheries crime. In fact a joint session between the IMCS network and FCWG to improve collaboration will be held later this year. Recent initiatives and networks, as Osterblom concludes, ‘provide a promising example of the capacity of the international community to mobilize responses to global and complex challenges’.

No comments yet.