Software Developed to Allow Quick and Easy Identification of Zebra

The stripes of a zebra are so unique that they are likened to human fingerprints.

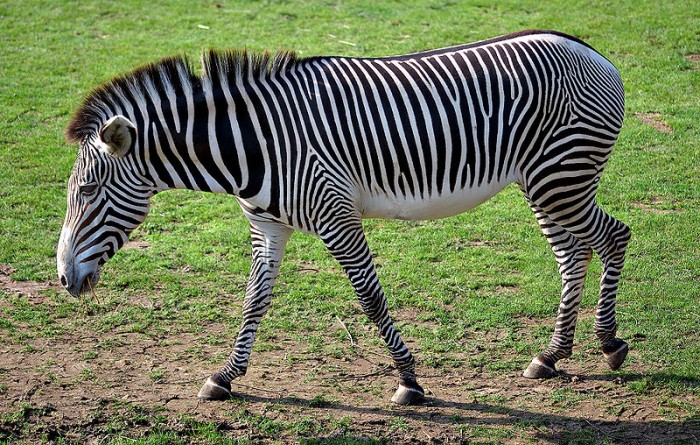

Image: By André Karwath aka Aka (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons

Image: By André Karwath aka Aka (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons Identifying zebras can be a laborious, inaccurate and complex process. The markings are not easy to recognise and the animals tend to run if humans get too close, meaning identification and therefore population estimates aren’t very reliable.

To solve this problem a team of US computer scientists and biologists have developed a system which can more accurately identify individual zebras. A photograph is taken of an individual and uploaded to a computer where a rectangle is drawn around the zebra’s flank. The stripes of a zebra are so unique that they are likened to human fingerprints. The rectangle is then divided into horizontal bands and each pixel is deemed either black or white, which creates a low resolution version of the stripes. These bands are called ‘StripeStrings’. Unlike a barcode, where each horizontal band is either completely black or completely white, a single StripeString is made up of a string of pixels. So a StripeString may have a pixel pattern: black, white, white, black, black etc., whereas a barcode stripe would be composed of a string of either all black or all white pixels. A collection of StripeStrings is termed a ‘StripeCode’ and the whole system is known as ‘StripeSpotter’. Once a database is compiled the system is able to match the StripeCode obtained from a photograph with the matching code stored in the database, thereby enabling identification. The system is also able to account for changes in perspective, exposure and body size between photographs of the same individual.

StripeSpotter is a free open-source system and is available to anyone. It can therefore be used to save time, and consequently valuable money, within many conservation projects, without the need to invest heavily in new technology. All that is needed is a camera, computer and internet connection. Obviously a database is needed for individuals to be identified. This will take time, but a database is already being built for plains and grevys zebra in Kenya. It is hoped that databases for other animals with distinct markings, such as tigers and giraffes, will be compiled in the future.

This technological advance is very exciting as it has the capability to improve population monitoring. This is turn leads to more conservation success by allowing more informed management actions to be taken.

The StripeSpotter website: http://code.google.com/p/stripespotter/

Use of StripeSpotter at a reserve in Kenya: http://www.lewa.org/wildlife-conservation/grevys-zebras-on-lewa/

No comments yet.