Finding New Homes Won’t Help Emperors

Many species can migrate to avoid the effects of climate change but a new study has shown that, while finding new homes may help Emperor penguins in the short term, by the end of the century their populations will face devastating declines.

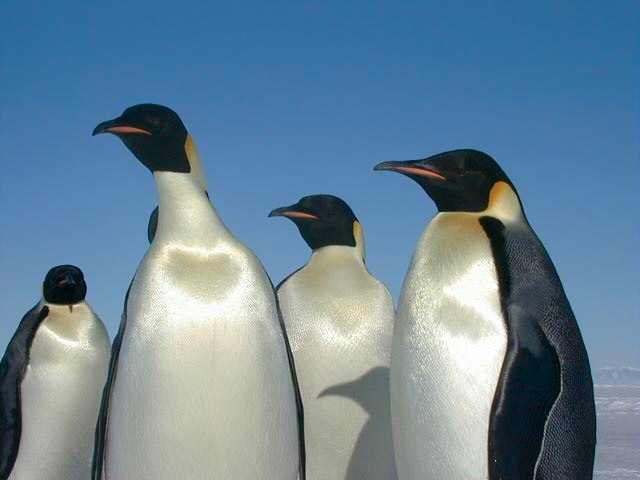

Image: By NSF/Josh Landis, employee 1999-2001 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Image: By NSF/Josh Landis, employee 1999-2001 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons If projections for the melting of Antarctic sea ice from now until 2100 are correct, the vanishing landscape will strip Emperor penguins of their breeding and feeding grounds, and put populations at risk. While other species under threat from climate change can migrate to escape the effects, a new study shows that dispersal will only help Emperors for a short time.

Scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute report in the journal Biological Conservation that, as sea ice conditions deteriorate, the 54 colonies that exist today will face devastating declines by the end of the century. This has led them to call for the Emperor penguin to be listed as an endangered species.

“We know from previous studies that sea ice is a key environmental driver of the life history of Emperor penguins, and that the fifty-percent declines we’ve seen in Pointe Géologie populations along the Antarctic coast since the 1950s coincide with warmer climate and sea ice decline,” said Stephanie Jenouvrier, WHOI biologist and lead author of the study. “But what we haven’t known is whether or not dispersal could prevent or even reverse future global populations. Based on this study, we conclude that the prospects look grim at the end of 2100, with a projected global population decline as low as 40 percent and up to 99 percent over three generations. Given this outlook, we argue that the Emperor penguin is deserving of protection under the Endangered Species Act.”

The relationship between Emperor penguins and sea ice is a fragile one – too little sea ice reduces the availability of breeding sites and prey, but too much means longer hunting trips for adults and thus lower feeding rates for chicks. It has only been in the past few years that scientists became aware of the penguins’ ability to migrate to locations with potentially more optimal sea ice conditions.

To determine whether migration would ultimately help the penguins defend against population decline, mathematicians helped to develop a demographic model of penguin colonies. This tracked the population connectivity between penguins as they take their chances moving to new habitats offering better sea ice conditions. The model factored in the penguins’ dispersal distance, behaviour and sea ice forecasts from climate projections.

“We saw sustained populations through 2036, at which point there was an ‘ecological rescue’ that reversed the anticipated decline expected without dispersion for about a ten-year period,” Stephanie Jenouvrier explained. “During that time, the penguins made wise choices in terms of selecting the highest-quality habitat they could reach. But the ‘rescue’ was only short-lived, and started plummeting in 2046. When we averaged out all the scenarios, the model painted a very grim picture through 2100, regardless of how far penguins travelled or how wise their habitat selections were.”

The scientists conclude that the accelerated pace at which the ice is melting in Antarctica, and the fact that climate change is not stationary, means that even if the penguins move to locations with better sea ice conditions, those conditions could change dramatically from one year to the next.

However, adding Emperor penguins to the Endangered Species list could help them. It would likely trigger new fishing regulations in the Southern Ocean and highlight the need for new global conservation strategies. It would increase public awareness as well as spur the need for more studies of Emperor penguins. “While we’ve learned that dispersal doesn’t change the ultimate fate of these animals we need to better understand the dynamics of what happens when they disperse. To do this, we’ll need to tag penguins from several colonies and monitor them. Eventually, we also want to understand if populations may eventually adapt to sea ice change, and more generally, how they will respond to the changing landscape in terms of breeding and other life history stages.”

One Comment

This is serious and must be taken into serious consideration. I have a passion for wildlife conservation especially those in the endangered species list. I come from a state with the largest forest cover in my country which is gradually depleting by the day due to illegal activities. I see the dangers being posed on the forest and Wildlife species there in. I want to do something but I am limited by my inability to find my self in an organization which give me the drive and power I need. Unfortunately I keep applying for conservation jobs but haven’t gotten a chance yet. I do hope and pray I get one soon to put in my best in this course.