Fingerprint Technology Aids Fight Against Pangolin Poaching

Forensic fingerprinting techniques will now be used in the fight against the illegal wildlife trade. The new techniques will allow fingerprints from pangolin scales to be lifted so poachers and smugglers can be brought to justice.

A pioneering new project trials fingerprinting techniques to battle pangolin poaching. Forensic fingerprinting techniques will now be used in the battle against the illegal wildlife trade as new methods of lifting fingermarks from trafficked animals have been developed.

Researchers at the University of Portsmouth and international conservation charity ZSL (Zoological Society of London), with support from the UK Border force, developed the technology with one particular animal in mind, the pangolin.

Pangolins are also known as scaly anteaters because of their appearance. Globally, there are eight species of pangolin distributed across the continents of Asia and Africa. The four found in Asia are the Indian Pangolin, Philippine pangolin, Sunda pangolin and Chinese pangolin, while the African pangolin species are black-bellied pangolin, white-bellied pangolin, giant ground pangolin and Temminck’s ground pangolin.

Around 300 pangolins are poached every day, making these unusual animals the most illegally trafficked mammals in the world. It has been estimated that as many as one million pangolins have been illegally traded within Asia in the past 10 to 15 years. Their meat is considered a delicacy in China and Vietnam – it is expensive and consumed to demonstrate status – while their scales are used in traditional Asian medicine. In fact, it was only in May 2015 that the Vietnam Government stopped pangolin scales being available under health insurance schemes, while China still has a domestic yearly quota of roughly 25 tonnes (equivalent to anywhere between 25,000-50,000 pangolins) of Chinese pangolin scales for medicinal use. They are also used in traditional African bush medicine.

Population crashes attributed to the current poaching epidemic within Asian pangolin populations has led to significant growth in export of scales from Africa. In light of this and the continued threat posed by the illegal trade, all eight pangolin species were uplisted to Appendix I at the most recent Conference of the Parties to CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species), in South Africa in September 2016.

Species on Appendix I are considered threatened with extinction and all trade in pangolin meat and scales is currently outlawed, other than in exceptional circumstances. This uplisting reflects the wide acceptance that populations for all pangolin species are in serious decline, with the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) listing all Asian pangolin species as either ‘Critically Endangered’ or ‘Endangered’ while the African species are all listed as ‘Vulnerable’.

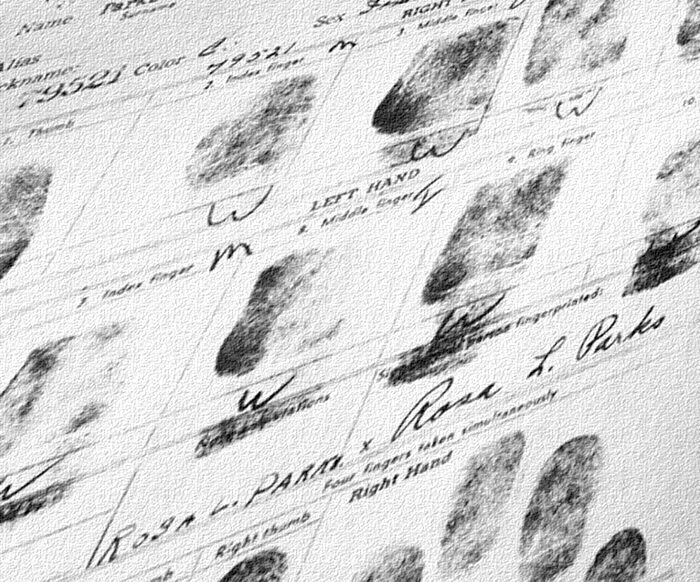

The new fingerprinting method uses gelatine lifters with a low-adhesive gelatine layer on one side, which are used universally by forensic practitioners for lifting footwear marks, fingermarks and trace materials off various objects in criminal investigations.

In a preliminary trial, the researchers tested the usability of gelatine lifters for visualising finger marks on pangolin scales. Using 10 pangolin scales from several species, supplied by UK Border Force, each scale was gripped by five participants. A gelatine lifter was applied to the scale, removed and scanned using a BVDA GLScanner system which provided 100 fingermarks (one from the front and one from the back of the scales).

The fingermarks were then graded for the presence of ridge detail on the University’s BVDA gel imaging scanner and 89% of the visualised gelatine lifts examined produced clear ridge detail. This means that law enforcement agencies will, potentially, be able to use the mark to identify persons of interest who have come into contact with the scale.

Dr Nicholas Pamment, who runs the Wildlife Crime Unit at the University of Portsmouth, says: “This is a significant breakthrough for wildlife crime investigation. Wildlife trafficking is a significant factor in the loss of habitats and species. While forensic science techniques are being used as part of the investigation process, there is a lack of research looking at ‘what works’ in the context, or within the limitations of the wildlife crime investigation and in the environments where the investigations take place. What we have done is to create a quick, easy and usable method for wildlife crime investigation in the field to help protect these critically endangered mammals. It is another tool that we can use to combat the poaching and trafficking of wild animals.”

Christian Plowman, Law Enforcement Advisor for ZSL, added: “This project is a great example of how multiple organisations are working together to not only develop methods that work, but to optimise the methods for use in wildlife crime investigations. The initial catalyst for this project were Dr Brian Chappell (University of Portsmouth) and I, both former Scotland Yard detectives, now working in conservation law enforcement for ZSL and the other in academia. This point of uniqueness underlines and enhances credibility for the project and for both organisations.”

“We know how prized pangolins are by those engaged in wildlife crime. I am delighted that Border Force has been able to play its part in the development of this method of lifting fingermarks from pangolin scales, technology which will help bring poachers and smugglers to justice,” said Grant Miller, Head of the UK’s National CITES Enforcement Team

The researchers have now developed gelatine lifter packs for Wildlife Rangers in Kenya and Cameroon to help in their fight against illegal poaching of pangolins. Each pack contains 10 gelatine lifters, scissors, insulating packs, evidence bags, a roller and a simple pictorial guide for the Rangers to follow. The field packs for the Kenyan wildlife service were initially provided for the examination of poached elephant ivory and dead elephants killed by poachers.

Jac Reed, Senior Specialist Forensic Technician at the University of Portsmouth, said: “What is fundamental to this method is its application, it is easy to use and employs low-level technology. This is so important for rangers in the field who need to be able to get good quality fingermarks very quickly to ensure their own safety. It is also important for law enforcement in developing countries who may not have access to more advanced technologies and expensive forensic equipment.”

No comments yet.