Ghost Fishing Threatens Species

Surveys along the length of the River Ganges, alongside interviews with local fishermen, have revealed that waste fishing gear is posing a serious threat to many species. A system that would provide fishermen to recycle their nets could be effective at preventing entanglement.

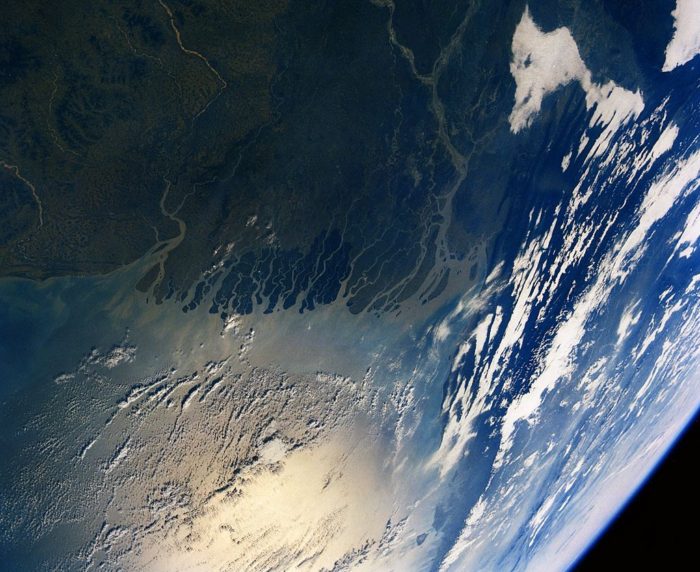

Image: NASA/exploitcorporations, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Image: NASA/exploitcorporations, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Waste fishing gear in the River Ganges poses a threat to wildlife including otters, turtles and dolphins, new research shows. The study, published in Science of the Total Environment, says entanglement in fishing gear could harm species including the critically endangered three-striped roofed turtle and the endangered Ganges river dolphin.

Surveys along the length of the river, from the mouth in Bangladesh to the Himalayas in India, showed that fishing nets, all made of plastic, were the most common type of gear found, and that levels of waste fishing gear are highest near to the sea.

Interviews with local fishers revealed high rates of fishing equipment being discarded in the river – driven by short gear lifespans and lack of appropriate disposal systems.

The study was led by researchers from the University of Exeter, with an international team including researchers from India and Bangladesh. It was conducted as part of the National Geographic Society’s “Sea to Source: Ganges” expedition.

Dr Sarah Nelms, of the University of Exeter’s Centre for Ecology and Conservation, said: “The Ganges River supports some of the world’s largest inland fisheries, but no research has been done to assess plastic pollution from this industry, and its impacts on wildlife. Ingesting plastic can harm wildlife, but our threat assessment focussed on entanglement, which is known to injure and kill a wide range of marine species.”

The researchers used a list of 21 river species of “conservation concern” identified by the Wildlife Institute for India. They combined existing information on entanglements of similar species worldwide with the new data on levels of waste fishing gear in the Ganges to estimate which species are most at risk.

Speaking about the why so much fishing gear was found in the river, Dr Nelms said: “There is no system for fishers to recycle their nets. Most fishers told us they mend and repurpose nets if they can, but if they can’t do that the nets are often discarded in the river. Many held the view that the river ‘cleans it away’, so one useful step would be to raise awareness of the real environmental impacts.”

National Geographic Fellow and science co-lead of the expedition Professor Heather Koldewey, of the Zoological Society of London and the University of Exeter, said the study’s findings offer hope for solutions based on “circular economy” where waste is dramatically reduced by reusing materials: “A high proportion of the fishing gear we found was made of nylon 6, which is valuable and can be used to make products including carpets and clothing. Collection and recycling of nylon 6 has strong potential as a solution because it would cut plastic pollution and provide an income. We demonstrated this through the Net-Works project in the Philippines, which has been so successful it has become a standalone social enterprise called COAST-4C. This is a complex problem that will require multiple solutions, all of which must work for both local communities and wildlife.”

No comments yet.