Glimmer of Hope for Amphibians

Conservationists have collected hundreds of amphibian species threatened by the fungus and are maintaining them in captivity with the hope to someday re-establish them in the wild.

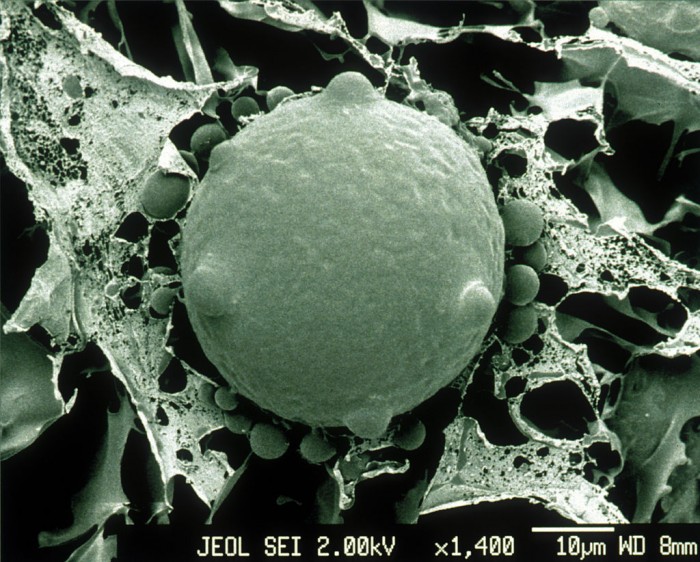

Image: CSIRO

Image: CSIRO The chytrid fungus is believed to be the cause of the greatest loss of biodiversity due to disease in recorded history. Currently, the disease spread by the fungus, called chytridiomycosis, threatens around 500 species worldwide and has contributed to population declines and several species extinctions. The disease disrupts amphibians’ skin, potentially resulting in death. However, some research studies published recently have offered a glimmer of hope.

One study by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and other organisations, published this month in PLoS ONE, found that climate change may make environmental conditions unsuitable for the chytrid fungus in some regions, potentially halting the spread of the disease. The study took place in Africa’s Albertine Rift, which extends along parts of Uganda, Rwanda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi and Tanzania, and is rich in wildlife. Initially, the scientists conducted a baseline survey of how the chytrid fungus was affecting amphibians in the region and found that it was widespread. They then modelled various scenarios under different climates and discovered that the range of the fungus will contract by 2080. They stated that the likelihood of chytrid occurrence is predicted to decrease during warmer periods, and when precipitation exceeds an annual rainfall threshold above 1,800mm per year.

“We infer that [chytrid] prevalence in the Albertine Rift may decrease as a result of climate change,” said the study’s lead author Dr. Tracie Seimon of WCS. “This is borne out by the modelling we have presented here, which indicates a major range contraction of habitat suitability for this fungus by the end of the century.” Nevertheless, the authors of the study also warn that climate change may still negatively affect amphibians in other ways, such as reducing habitat availability.

But other good news presented by the study is that microscopic examination of amphibians did not reveal the presence of the disease in the majority of the frogs that are infected with the chytrid fungus. This indicates that these frogs may be regionally resistant to the disease. Co-author Dr. Denise McAloose, chief pathologist at WCS, said: “While chytrid is wiping out amphibians worldwide, there may be some resistance of amphibians in the Albertine Rift to this organism. However, further study is needed to better understand resistance to other strains with different pathogenicity, or the potential for environmental triggers such as seasonal variations to make frogs more susceptible to current strains.”

The scientists also discovered that there is a long history of the chytrid fungus in the Albertine Rift. They took samples from museum specimens of amphibians which showed that the earliest record of the fungus came from an Itombwe River frog collected in 1950 in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The long history of the fungus, combined with the study’s findings of the frogs being in relatively good health, gives hope that the frogs in this part of Africa are “somewhat resistant” to the disease.

The baseline data the scientists collected, combined with the modelling predications, will be important for future comparative studies, especially if there are significant changes in amphibian health or climatic conditions. “The Albertine Rift is one of the world’s hotspots for amphibian biodiversity, and is also one of the most threatened,” said Dr. Seimon. “Baseline data on [chytrid] can help to form a more complete picture of the presence and significance of this fungus and help guide and inform discussions on climate and species-related conservation strategies at both the local and global levels.”

Another study, by scientists from Virginia Tech, has shown that the naturally occurring bacteria on a frog’s skin could be an important tool for helping the animal fight off deadly chytridiomycosis. The scientists demonstrated that the fungus affects the microbial structure of bacteria on a frog’s skin, but the bacteria can actually respond to infection and adjust structure and function to compensate for it. It is not one bacteria, but rather the whole bacterial community that is important for the health of the frog. The next step will be to further explore the capabilities of other naturally occurring bacteria and discover which environmental factors allow some frogs’ bacteria to successfully fight off the fungus.

“Chytrid disease is devastating large numbers of amphibian communities in many parts of the world,” said Simon Malcomber, programme director in the National Science Foundation’s Division of Environmental Biology, which funded the research. “The study shows the importance of amphibian microbiomes in mediating the effects of chytrid disease, and offers hope of limiting the infection.”

Another study, published in Nature by scientists from the University of South Florida, revealed that amphibians can acquire behavioural or immunological resistance to chytrid fungus. One experiment detailed in the study showed that after just one exposure to the fungus, frogs learned to avoid the pathogen. In subsequent experiments in which the frogs could not avoid the fungus, the frog’s immune responses improved with each fungal exposure and infection clearance, significantly reducing fungal growth and increasing the likelihood that the frogs survived subsequent chytrid infections.

“The amphibian chytrid fungus suppresses immune responses of amphibian hosts, so many researchers doubted that amphibians could acquire effective immunity against this pathogen. However, our results suggest that amphibians can acquire immunological resistance that overcomes chytrid-induced immunosuppression and increases their survival,” said Jason Rohr, an associate professor of integrative biology. “Immune responses to fungi are similar across vertebrates and many animals are capable of learning to avoid natural enemies. Hence, our findings offer hope that amphibians and other wild animals threatened by fungal pathogens – such as bats, bees, and snakes – might be capable of acquiring resistance to fungi and thus might be rescued by management approaches based on herd immunity,” he added

“The discovery of immunological resistance to this pathogenic fungus is an exciting fundamental breakthrough that offers hope, and a critical tool for dealing with the global epidemic affecting wild amphibian populations,” says Liz Blood, programme officer in the National Science Foundation’s Directorate for Biological Sciences, which funded the research.

Conservationists have collected hundreds of amphibian species threatened by the fungus and are maintaining them in captivity with the hope to someday re-establish them in the wild. Reintroduction efforts so far have failed because of the persistence of the fungus at the collection sites, but these studies prove all is not lost, and provide glimmers of hope for the future survival of amphibians throughout the world.

No comments yet.