Link Between Amphibian Disease and Climate Change

New research has been published that shows that climate change will make the impact of the chytrid fungus disease worse. Already at high altitudes, frogs and toads are being infected at increasingly high rates.

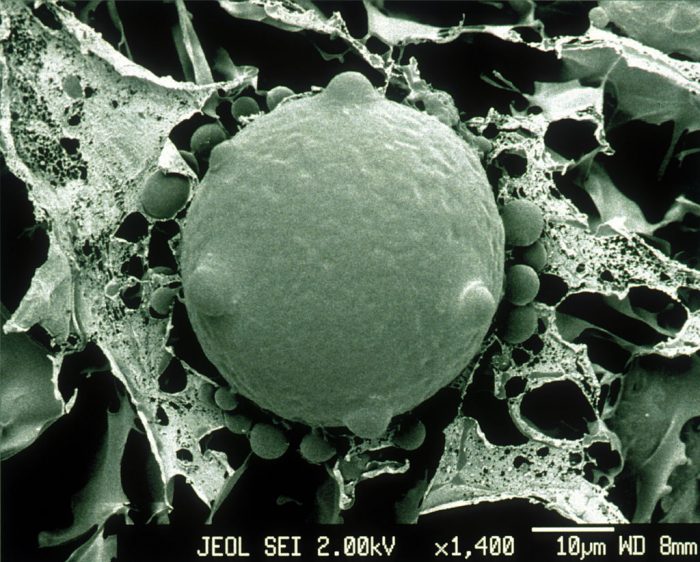

Image: Dr Alex Hyatt, CSIRO

Image: Dr Alex Hyatt, CSIRO Despite the good news of my last blog on the recovery of the Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frog populations in the face of chytrid fungus, new research has been published that shows that climate change will make the impact of the disease worse.

At high altitudes, frogs and toads are being infected at increasingly high rates in the Pyrenees Aspe Valley in France – a spike in mortality that is blamed on temperature rises in these mountains. An eight year study published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B by researchers at Imperial College London and the Zoological Society of London, is the first to compare temperature with amounts of disease. It follows years of speculation that climate change was driving deaths by chytrid.

From analysis of lake melt and amphibian infection rates, the researchers found that the earlier the valley’s lakes melted in the springtime, the higher the rates of infection for both frogs and toads. They then created predictive climate models that focused on regional temperatures across this part of the Pyrenees. The research predicted that the region will continue to warm significantly and that frozen lakes will become increasingly rare.

This means that midwife toad tadpoles in these lakes will spend much less time under ice. Infection of chytrid is very common in midwife toad tadpoles, but is kept in check by low temperatures and frozen lakes. Yet with warming temperatures causing lakes to melt earlier, other species of amphibians will be exposed to the midwife toads and will be less able to cope with the spillover effects of infection.

Professor Matthew Fisher from the School of Public Health at Imperial and co-author of the study, said: “These findings show yet another devastation of species thanks to human activity. Thankfully, it’s unlikely the midwife toads will suffer extinction, largely because temperature is altitude dependant and so the toads in lower areas will survive. The rapid decline of midwife toads in these regions will affect the whole local ecosystem in ways we can only guess at present. Food webs are likely to become less stable – and we are losing an Eden-like biodiversity in these mountains thanks to humanity’s impact on the natural environment.”

At present, researchers at Imperial College London and the Zoological Society of London are able to cure the infection on a small scale in a lab, but their methods so far have not been translated to the large scale of the Aspe Valley. Professor Fisher added: “Until we know why this happens, it will be difficult to find a solution. Further research should aim to explain why warming temperatures are driving these deaths in midwife toads.”

No comments yet.