A-Z of Invasive Marine Species: Darwin’s Barnacle

Acorn barnacles are found in one of the severest conditions on the coast – rock faces on exposed beaches. On top of this, most tend to live high on the upper shore where they are uncovered for long periods of time by the tide.

Image: By Auguste Le Roux (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

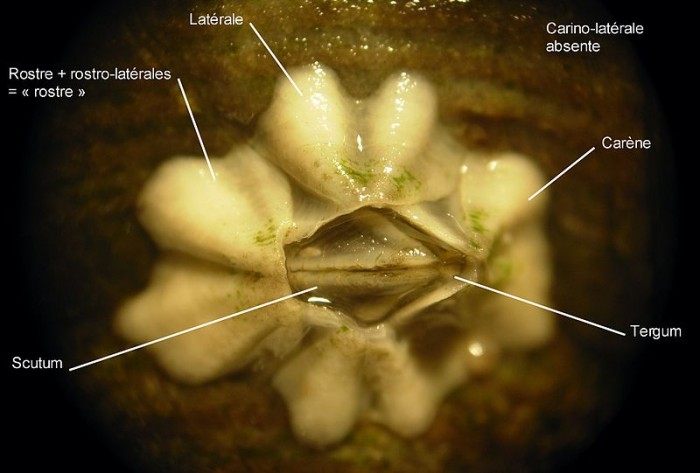

Image: By Auguste Le Roux (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons This week, D is for Darwin’s Barnacle (Elminius modestus), otherwise known as the acorn barnacle. E. modestus is a small barnacle, 5-10 mm in diameter, and it is identified by having only 4 calcified shell plates (where as native shore species usually have 6 plates). Darwin’s barnacles have a low and conical body shape, another identifying feature is their large diamond shaped opercular aperture (two pairs of ‘bony’ plate that closes when the tide goes out). In the younger individuals, the plates of the shell are smooth with an indentation in the centre. Whereas, the older barnacles have vertical ridges through the shell plates. This can give the older barnacles an irregular shape. The shells also change colour as the barnacles age. The younger individuals are white and become an eroded grey/brown colour as they get older.

Acorn barnacles are found in one of the severest conditions on the coast – rock faces on exposed beaches. On top of this, most tend to live high on the upper shore where they are uncovered for long periods of time by the tide. Here they are open to the full severity of the weather, the cold in winter and the heat in summer when they are threatened with desiccation (drying out). This is a risky strategy as barnacles are stuck to the rock face and cannot move to shelter when conditions worsen. It is found on the upper middle shore and is tolerant of low salinity levels where fresh water enters the sea. In order to survive the heat they pull their top plates (operculum) together so reducing evaporation from the inside of the shell. However, this technique is not fool proof as in hot summers even mature adults can die. They also still have absolute reliance on the sea, as they have to be covered by the tide to feed and spawn.

Barnacles are hermaphroditic however it is normal at the time of mating that barnacles will take on the role of either male or female. The eggs are stored in the female until they hatch and are released as free swimming larvae known as nauplii, which join other plankton, floating with the currents. The nauplii then go through several moults until they metamorphose into a cyprid, at this stage it is still free swimming but it cannot feed. It is at this stage it looks for a suitable place to fix itself; which it does, head first. The plankton growth stages allow the species the possibility to expand its range. After fixing the barnacle metamorphoses again into a small adult.

E. modestus originated in Australia and was first seen in British waters during the Second World War, in Chichester Harbour. It is believed to have arrived on the hulls of ships, or possibly the larval stages have travelled in bilge water. It has become a common sight in southern England and Wales and is spreading northwards, but the spread may be limited by the cold temperatures of our shore. It had reached the Scottish Borders by 1960 and Shetland by 1978. It is found on the Atlantic coasts of Europe from Gibraltar to Germany. E. modestus not only competes with endemic British species, particularly Balanus balanoides, but has colonized some sheltered and estuarine habitats that have not previously been inhabited by barnacles.

No comments yet.