Conservationists May Spread Pathogens

A common conservation strategy is to move individual animals from one location to another to boost population numbers and restore ecosystems. However, a new study shows that the dangers of this may, in fact, outweigh the risks.

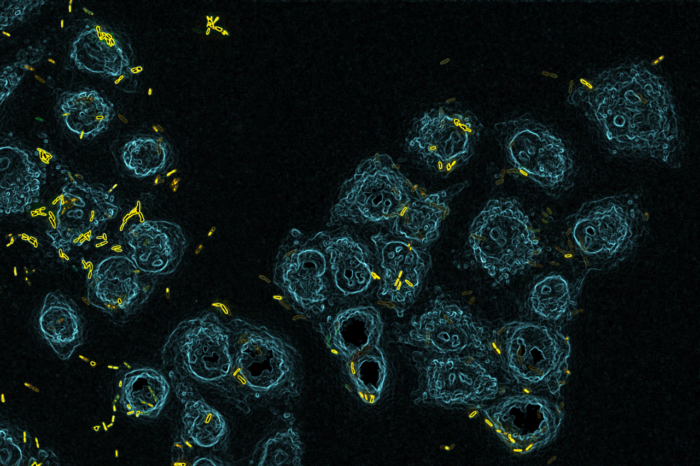

Image: Benoit-Joseph Laventie, CC BY 4.0

Image: Benoit-Joseph Laventie, CC BY 4.0 Moving endangered species to new locations is often used as part of species conservation strategies and can help to restore degraded ecosystems. But scientists say there is a high risk that these relocations are accidentally spreading diseases and parasites.

A new report published in the journal Conservation Letters focuses on freshwater mussels, which the researchers have studied extensively, but is applicable to all species moved around for conservation purposes.

Mussels play an important role in cleaning the water of many of the world’s rivers and lakes but are one of the most threatened animal groups on Earth. There is growing interest in moving mussels to new locations to boost threatened populations, or so they can be used as ‘biological filters’ to improve water quality.

A gonad-eating parasitic worm which can leave mussels completely sterile, was identified as a huge risk for captive breeding programmes where mussels from many isolated populations are brought together.

Dr David Aldridge in the Department of Zoology at the University of Cambridge and senior author of the report said: “We need to be much more cautious about moving animals to new places for conservation purposes, because the costs may outweigh the benefits. We’ve seen that mixing different populations of mussels can allow widespread transmission of gonad-eating worms – it only takes one infected mussel to spread this parasite, which in extreme cases can lead to collapse of an entire population.”

Pathogens can easily be transferred between locations when mussels are moved. In extreme cases, the pathogens may cause a population of mussels to completely collapse. In other cases, infections may not cause a problem unless they are present when other factors, such as lack of food or high temperatures, put a population under stress leading to a sudden outbreak.

The report recommends that species are only relocated when absolutely necessary and quarantine periods, tailored to stop transmission of the most likely pathogens being carried, are used.

It identifies four key factors that determine the risk of spreading pathogens when relocating animals: proportion of infected animals in both source and recipient populations; density of the resulting population; host immunity; and the life-cycle of the pathogen. Pathogens that must infect multiple species to complete their life-cycle, like parasitic mites, will only persist if all the species are present in a given location.

“Moving animals to a new location is often used to protect or supplement endangered populations. But we must consider the risk this will spread pathogens that we don’t understand very well at all, which could put these populations in even greater danger,” said Josh Brian, a PhD student in the Department of Zoology at the University of Cambridge and first author of the report.

Different populations of the same species may respond differently to infection with the same pathogen because of adaptations in their immune system. For example, a pack of endangered wolves moved to Yellowstone National Park died because the wolves had no immunity to parasites carried by the local canines.

The researchers say that stocking rivers with fish for anglers, and sourcing exotic plants for home gardens could also move around parasites or diseases.

Also involved in the study was PhD student Isobel Ollard. She adds: “Being aware of the risks of spreading diseases between populations is a vital first step towards making sure we avoid unintentional harm in future conservation work.”

No comments yet.