Recovery of Yosemite’s Yellow-legged Frog

A study shows that after decades of decline (and despite continual exposures to stresses such as non-native fish, disease and pesticides) the frog’s abundance across Yosemite has increased seven-fold.

What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger is an old adage that seems to hold true for the Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frog. Its remarkable recovery in the face of many threats has been documented in an expansive, data-rich study of the species in Yosemite National Park.

The study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows that after decades of decline (and despite continual exposures to stresses such as non-native fish, disease and pesticides) the frog’s abundance across Yosemite has increased seven-fold. This equates to an annual rate of increase of 11% over the 20-year study period. These increases, occurring over a large landscape and across hundreds of populations, provides a rare example of amphibian recovery at an ecologically relevant scale.

“We now have a parkwide picture of what’s happening in Yosemite, and it shows convincingly that these frog populations are increasing dramatically,” said lead author Roland Knapp, a biologist from University of California Santa Barbara. “These new results show that, given sufficient time and the availability of intact habitat, the frogs can recover despite the human-caused challenges they face.”

The yellow-legged frogs were once a common sight across the park but have disappeared from more than 93% of their historical locations. The study analysed more than 7,000 frog surveys at hundreds of sites to find out the species’ current predicament. “With this unprecedented, robust data set, we could look for patterns in frog population trends, and potential factors that might be influencing frogs in Yosemite,” Gary Fellers from the US Geological Survey said. “Fortunately, and unexpectedly, we found that in spite of a host of potential factors that could be working to depress or eliminate frog populations, the overall pattern has been for a slow, but widespread recovery of Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frogs.”

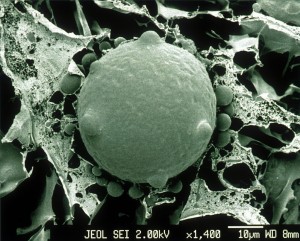

One of these factors is the deadly fungal disease chytridiomycosis, which affects amphibians throughout the world and has caused at least 200 species of frogs and salamanders to become extinct within the last 30 years. To understand why frogs in Yosemite could have recovered despite this ongoing threat, the study also includes a laboratory experiment. This demonstrated that these frogs, which have been exposed to the disease for decades, are less susceptible than frogs from populations that are naïve to the disease.

This suggests that the frogs have evolved at least partial resistance to the disease, although the exact mechanism that leads to reduced susceptibility remains a mystery. “We are working to identify those mechanisms. That information will be critical to recovery efforts not just for yellow-legged frogs but also for other amphibians worldwide that are endangered by chytridiomycosis.”

No comments yet.