Canine Distemper Confirmed in Endangered Big Cat

Infection with canine distemper virus has joined the long list of threats to the endangered Amur leopard, with the first documented case having been identified in a 2 year old female.

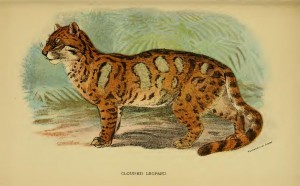

Image: William Warby (Flickr) [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]

Image: William Warby (Flickr) [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)] The Far Eastern or Amur leopard is already among the rarest of the world’s big cats, but new research reveals that it faces yet another threat: infection with canine distemper virus (CDV). A new study published in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases describes the first documented case of CDV in a wild Amur leopard.

The Amur leopard is a nocturnal animal that lives and hunts alone – mainly in the vast forests of Russia and China. It is able to survive in the harsh winters thanks to the hairs of its unique coat that can grow up to 7.5cm long. And it is because of their coat that they are a target for poachers. However, over the years the Amur leopard hasn’t just been hunted mercilessly (alongside its prey species – roe deer, sika deer and hare for example), its homelands have been gradually destroyed by unsustainable logging, forest fires, road building, farming, and industrial development. It is estimated that only 70-80 individuals remain. This tiny population is therefore also extremely vulnerable to inbreeding depression, natural catastrophes and disease. But Amur leopards are top predators in their landscape, so they play a crucial role in keeping the right balance of species in their area. That also affects the health of the forests and wider environment, which provides local wildlife and people with food, water and other resources.

With numbers so low and their role in the ecosystem so important, every single Amur leopard is precious. The case of CDV reported in the study involved a two-year-old female leopard that was found along a road that crosses the Land of the Leopard National Park, in the Russian territory of Primorskii Krai.

“The leopard was extremely sick when she was brought in, and had severe neurological disease,” said Ekaterina Blidchenko, veterinarian with the National Park and the TRNGO Animal Rehabilitation Center. “Despite hand-feeding and veterinary attention, her condition worsened, and a decision was made to euthanise her for humane reasons.”

Although CDV is well known in domestic dogs, and wolves and foxes, it also infects a wide range of carnivore species, including big cats like lions, tigers and leopards, as well as raccoons, skunks, pandas, pinnipeds, some primates and other animals. In 1994, a CDV outbreak in Tanzania killed over 1,000 lions in the Serengeti National Park. Researchers suspect that the lions may have contracted distemper from the many dogs kept by local tribesmen. The disease, which is distinct from feline distemper virus that affects small domestic cats, almost wiped out the endangered black-footed ferret in Wyoming a decade ago. Symptoms include thick nasal discharge, watering eyes, inflammation of the lungs and other organs, and damage to the nervous system displayed as twitching and walking in circles.

Nadezhda Sulikhan, a scientific staff member of Land of the Leopard National Park and Ph.D. candidate at the Federal Scientific Centre of East Asia Terrestrial Biodiversity (part of the Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences), says: “The leopard virus was genetically similar to infections we’ve diagnosed in wild Amur tigers. But we think these infections have spilled over from a disease reservoir among domestic dogs, or common wild carnivores like badgers and foxes.”

Unlike the situation for a social species like lions, outbreaks of CDV are likely to spread more slowly among more solitary cats like leopards and tigers. However, even infrequent transmission can have profound consequences for the species concerned. Research has estimated that extinction of small populations of tigers is 65% more likely when they’re exposed to CDV.

Globally, carnivore populations are being pushed into smaller and more fragmented islands of habitat. If these trends continue, infectious diseases are likely to become a greater threat to carnivore survival in the future.

“As carnivore numbers decline, they face a greater risk from chance events like outbreaks of disease. With such a limited breeding population, even a small number of deaths from disease can be the difference between the survival of a population or extinction,” explains Dr. Martin Gilbert, Wildlife Health Cornell Carnivore Specialist with Cornell University’s College of Veterinary Medicine.

The combined pressures of habitat degradation, hunting and prey depletion have already marginalised this subspecies to a single population of approximately 70 to 80 individuals along the border of the Russian Far East and neighbouring northeast China. Conservationists now need to understand the severity of this new-found threat, and also where it is coming from, as this information is critical for developing measures that counter the disease’s impact.

Said Dr. Sulikhan: “Until we know where the virus is coming from, it is impossible to target vaccinations or other interventions to prevent infections in leopards. We are now working to unlock this riddle, and understand the importance of domestic dogs versus wild sources of the virus.”

For now, the most effective way to combat this new disease threat is through traditional carnivore conservation approaches; reducing hunting and protecting habitat.

Dr. Dale Miquelle, Director of the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Russia Program and co-author of the paper, said: “By increasing the size and connectivity of leopard populations, they become more able to cope with losses from infectious disease, vastly reducing the risk of extinction.”

Tatiana Baranowska, Director the Land of the Leopard National Park which holds the majority of Far Eastern leopards left in the world, said: “We are doing our utmost, in concert with our Chinese colleagues, to improve and expand leopard habitat to enlarge the existing population. Although disease and other threats are looming, we have great hope that our current and planned efforts will secure a future for this unique big cat.”

No comments yet.