Our Amphibians are in trouble, and they need you.

You would be forgiven for thinking, that given the somewhat exotic nature of species lost already, that this was, in fact, a tropical problem, though you would be wrong. And Britain’s amphibians too find themselves in hot water.

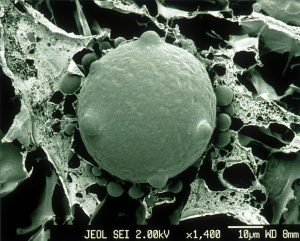

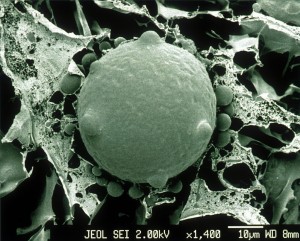

Image: By Richard Bartz, Munich aka Makro Freak Image:MFB.jpg - Own work, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4336610

Image: By Richard Bartz, Munich aka Makro Freak Image:MFB.jpg - Own work, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4336610 Tales of localised and even global extinctions are, unfortunately, rather common in the amphibian world. Particularly in current times as humans continue to ignorantly erode biodiversity on a global scale. From the endearing Rabbs’ Tree Frog, recently declared extinct after the last known individual died in captivity, to the similarly alluring Golden Toad. Amphibians are in trouble the world over: due to habitat loss, development, invasive species and the spread of deadly Chytrid fungus. You would be forgiven for thinking, that given the somewhat exotic nature of species lost already, that this was, in fact, a tropical problem, though you would be wrong. And Britain’s amphibians too find themselves in hot water.

Perhaps the most topical example of our ailing amphibian populations is the Common Toad, a beloved fixture of the British countryside which has now declined by 70% nationwide. In the last 30 years alone. The cause of this thought to stem predominately from habitat loss – the breeding ponds on which the toads depend drained to make way for the advance of agriculture and human habitation, with their foraging habitat similarly besieged. Traffic too has played a part, with many and more toads squashed on roads as they make their annual pilgrimage to and from the few remaining ponds, and pesticides and agricultural run-off poisoning many of those who do make it. It is all very bleak, with such things, sadly, not limited to Common Toads alone. The similar yet much scarcer Natterjack Toad, a resident of sand dunes and other coastal ecosystems, likewise threatened by the loss of said ecosystems. The species now clinging on in only handful of sites around the British coastline – subject to rigorous conservation measures to stop it sliding further towards the brink.

Even our most abundant amphibian species, the Common Frog is in trouble. Declining by up to 80% in some locations due to the spread of ranavirus, and thought to be declining, albeit to a lesser extent than our toads, nationwide. The loss traditional ponds, both in gardens – where they are often replaced by decking and overly manicured lawns – and further afield. A woeful trend also apparent in our newts with the iconic Great Crested Newt, despite being rigorously protected, still subject to substantial threats. From the destruction of habitats for development, from the introduction of exotic fish species for angling purposes, from the natural succession of ponds to grassland and, of course, habitat fragmentation. The select few sites lucky enough to still hold functional newt populations often separated from one another by miles and a great deal of often impassable roads. Indeed, with the smaller Palmate Newt also suffering declines across its range, only two native species appear to be somewhat stable at present – the Smooth Newt and the Pool Frog. The latter given a helping hand through deliberate reintroductions.

Like them or loathe them – bonkers but some do – our amphibians play an important role in many ecosystems, comprising a vital link in many food chains and acting as an indicator of ecosystem health. Their decline, and in some cases, predicted loss, does not bode well for our countryside. Though, mercifully, said populations have not declined to such an extent to fall beyond hope, and there are a number of things everyday people can do to help combat the trend. The obvious option being to build a garden pond – for frogs, toads and smooth newts – the size and extent of which is of little consequence, with all such water bodies providing a valuable oasis for our embattled amphibians. Allowing your garden (or at least a portion of it) to grow wild also helps, providing habitat for the various species on which amphibians depend for food, while a humble log-pile can also provide a valuable resource. Indeed, a quick check of my recently refurbished mound resulted in the discovery of all three common garden species – it really does work. Withholding the use of damaging pesticides, particularly in the vicinity of known amphibian populations, is also vital.

Of course, if you are unable to commit to any of the above, or indeed have already done so and wish to do more, you can help fund the great work of conservationists working to protect our amphibian friends. Froglife are a good place to start. There vital work to protect our frogs, newts and toads entirely dependent on the generosity of the public. So please, whether you choose to actively fund conservation measures or install your own, be sure to do something. Many of the species listed above are suffering, largely due to our own actions, and need all the help they can get. That is if they are to survive to croak and delight for another day.

One Comment

I have kept ponds wild life and fish, since 2007. Every year around last week of February I hear the Croaking of hundreds of Frogs, followed by gallons of spawn. As of today 5th March 2021, I have not seen a single frog. I am very worried that something has wiped them out? Liverpool L16